上報 Up Media

toggle- 最新消息 不斷更新/【世棒四強賽】「中華隊 vs 美國」中華隊9局三上三下未建功 暫以8:2領先 2024-11-22 14:17

- 最新消息 清華大學擬併中華大學 將設「清華平方科技園區」發展半導體 2024-11-22 13:51

- 最新消息 英王查爾斯三世加冕禮花費高達29.5億元 逾半民眾表態反對政府買單 2024-11-22 13:48

- 最新消息 【京華城弊案】朱亞虎200萬交保 李文宗11/26開延押庭 2024-11-22 13:30

- 最新消息 【世棒四強賽】峮峮也來了! 啦啦隊女神團美到登上東京巨蛋大螢幕 2024-11-22 13:10

- 最新消息 「巴西川普」波索納洛涉嫌政變 與4將軍企圖毒死或炸死正副總統 2024-11-22 12:50

- 最新消息 賴清德總統任內首次出訪選擇南太 黨政人士曝戰略考量 2024-11-22 12:40

- 最新消息 《大夢歸離》侯明昊錄真人秀在非洲草原拉屎 全程被外國遊客拍下秒登熱搜糗爆 2024-11-22 12:34

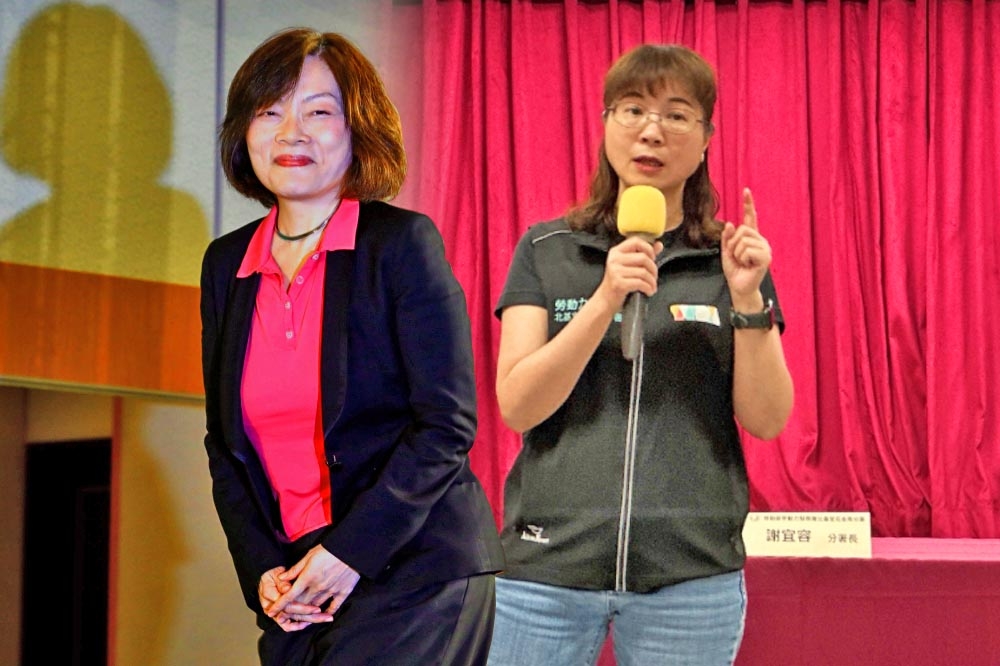

- 最新消息 【有片】露面了!謝宜容鞠躬道歉 落淚稱對不起家屬:孩子成冷冰冰遺體 2024-11-22 12:20

- 最新消息 美特使還在以色列進行調停 以軍持續對黎巴嫩空襲釀47死 2024-11-22 12:03

美助卿史達偉「不稱台灣為國家」 外交部:五度對台軍售已反映美國的支持

美國亞太助卿史達偉(David Stilwell)表示,美國會遵守「一法三公報」,且不會稱台灣為國家。(湯森路透)

美國亞太助卿史達偉(David Stilwell)2日出席研討會時表示,他自上任後很快訪問日本等亞太盟友,以展現美國對區域盟友承諾,但對於是否訪台,他表示美國會遵守「一法三公報」,且不會稱台灣為國家。

對此,外交部發言人歐江安3日表示,美方已多次重申對台灣的安全承諾,也已經五度對台軍售,充分反映美國對台灣的一貫堅定支持。

史達偉2日出席美國智庫布魯金斯學會「中國大陸在東亞角色」研討會,談及多元主義,並說:「中國強迫意識形態一致性的行動不只限於中國境內,針對大家普遍關切的議題,也就是各國將被迫在美國和中國之間做選擇,我想讓各位知道,美國不會強迫各國做這樣的選擇。當我們說美國的願景是多元與包容時,我們是認真的,而且過去紀錄也證實這點,美國並不希望指使他人,也不希望我們的盟友受到別人的指使。」(史達偉發言全文請詳見文末)

而被媒體詢問到「你提到先前曾參訪日本與其他國家以展現美國的支持,請問是否也會訪問台灣,以展現美國對台支持?」

史達偉回應:「答案很簡單,你剛才提到『國家』,而美國遵守「一法三公報」(臺灣關係法、上海公報、建交公報、八一七公報),我將遵從也支持此一政策,而且我不會稱台灣為國家。」

對此,歐江安3日表示,台美關係緊密友好,自川普政府上任後,美方已多次重申《台灣關係法》及「六項保證」履行對台灣的安全承諾。此外美方已經五度對台軍售,充分反映美國對台灣的一貫堅定支持。

歐江安提到,史達偉對台灣友好,此外美國政府高層,如副總統彭斯(Mike Pence)及國務卿龐培歐(Mike Pompeo),均曾在公開演說中肯定台灣的民主自由對國際社會貢獻。

歐江安強調,中華民國台灣是主權獨立國家,我國的民主、自由、人權及法治發展等成就,也獲得理念相近國家及國際社會的高度肯定。

歐江安表示,我方將秉持互信、互惠及互利的原則,在良好互動基礎上,以穩健務實的態度與美方深化全面性的台美合作夥伴關係。(中火再挨罰300萬)

史達偉發言全文:

Good afternoon. Thank you to the Brookings Institution for inviting me.

I’ve been asked to speak today about the People‘s Republic of China, and its intentions for shaping the global order.

I will do so by quickly reviewing our policy, and then drawing out a theme that keeps coming to mind as we consider the challenge. That theme is pluralism.

CHINA POLICY OVERVIEW

First off, let’s talk policy. It’s obvious that the Trump Administration has made long-overdue changes to U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific region. China is a major consideration, but so is our relationship with a diverse set of like-minded allies and partners.

Forty years ago, the PRC began to grow from its ideologically self-imposed isolation and economic weakness. “Reform and opening”—emphasis on “opening”—required the Chinese Communist Party to adapt to the larger region and world in order to benefit from multilateralism. We all understood that it would take time, but we were encouraged by significant progress in the 1980s.

There were many hopeful signs: My first trip to Beijing, in 1988, saw the beginnings of private enterprise, and the human energy and creativity it unleashed, in the form of a small dumpling restaurant just south of Tiananmen Square. You knew it was different because instead of regarding customers as a bother, this experimental shop actively sought out customers. The dumplings were hot, the beer was cold and the service was excellent, especially when compared with the state-owned restaurant next door.

Given these initial hopeful signs, U.S. policy for many years was largely premised on a version of the Golden Rule. American officials hoped that demonstrating the benefits of openness would move Beijing onto a more liberal path that led to greater economic and political openness.

But it has become clear that many of our hopeful assumptions were wrong. Twenty years of empty post-WTO assurances that “China will continue to work toward greater openness” have triggered an overdue rethink of the PRC, its ambitions, and our response. This administration now is addressing the PRC as it is, not as we long wished it would be.

What we have seen over the past two decades is that liberal reform has slowed and even reversed. As the PRC gained greater wealth and power, and grew more integrated with the world, it did not converge with the free and open global order as expected. Instead the Chinese Communist Party hopes to reshape the international system to become more compatible with its own authoritarian practices.

The Trump Administration has been clear that, even as our relationship with the PRC is competitive, we welcome cooperation where our interests align. Competition need not lead to confrontation or conflict. We have a deep respect for the Chinese people and there is a long history of cooperation as trading partners and even as allies—a legacy that got me interested in China in the first place.

And so our aim is to defend U.S. sovereignty, advance our regional interests, and promote the free, open, and rules-based order in Asia and worldwide.

THE CENTRALITY OF ‘PLURALISM’

Now the recent shift in U.S. perceptions and policy has triggered questions. If the “responsible stakeholder” notion has been overtaken by reality, what replaces it? We know Washington is against aggressive or threatening conduct by Beijing, but what is Washington for? In competing with the PRC, is Washington forcing countries to choose?

The word “pluralism” is not the complete answer to all such questions, of course. But it helps us address all of them because it captures something essential about what we mean when we talk about divergent visions of world order.

In dictionary terms, pluralism is about the coexistence of multiple things—whether states, groups, principles, opinions, or ways of life. In short: diversity, openness.

My point, in diplomatic terms, is that America’s foreign-policy vision, which is rooted in democratic pluralism at home, supports a corresponding pluralism abroad, too – in the Indo-Pacific region and across the world. Both at home and abroad, we support pluralistic systems governed by freedom, rule of law, and respect for the rights of one’s neighbors. And just as our vision of pluralism at home is rooted in the sovereign rights of individuals, so our vision of pluralism abroad is rooted in the sovereign rights of states.

This has been America’s vision for generations. Our challenge today, as in the past, is that the appreciation of pluralism is not universal, so we must come to its defense.

We have all heard about a “new type” vision of global governance. It denigrates pluralism, even though the existing system has served the world—China included—very well in the seven decades since World War II.

Let’s examine the details.

The United States supports a pluralistic Asia.

A pluralistic Asia is one in which the region’s diverse countries can continue to thrive as they wish. They are secure in their sovereign autonomy. They are free to be themselves, as Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yew put it. No hegemonic power dominates or coerces them.

In a pluralistic Asia, countries enjoy open and shared use of the global commons. International waters and airspace belong to all. No one country can convert them into a sole possession or a zone of exclusion.

Pluralism is essential to our vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific, as President Trump said in Da Nang two years ago: Countries in the region should remain a diverse constellation of stars, each shining brightly, and none a satellite to any other.

It is important to recognize that the region’s countries cherish that vision for themselves.

We know this, for example, from the recent ASEAN Outlook on Indo-Pacific, which emphasizes “inclusivity” to urge respect for all the region’s nations, large and small. We know it from the ASEAN Charter, which calls for upholding the principle of “unity in diversity.”

And we know it from Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific vision, South Korea’s New Southern Policy, India’s Act East policy, and Australia’s Indo-Pacific concept: All focus on broadening ties among all nations, based on rule of law and respect for sovereignty, with shared access to the commons and shared prosperity.

The United States supports pluralism not just in the Indo-Pacific, but around the globe.

After World War II, the United States led in the creation of a postwar international order that was pluralistic and free to an unprecedented degree. Following the flawed peace of World War I, the post-World War II system was designed to benefit victors and vanquished alike, giving all an equal voice in an international forum. Those arrangements aimed to prevent a new world war by ensuring that peace and prosperity could be shared. As with all human endeavors, it falls short of perfection, but overall it has been a stunning success.

As President Trump has said in addressing the United Nations: “It is an eternal credit to the American character that even after we and our allies emerged victorious from the bloodiest war in history, we did not seek territorial expansion, or attempt to oppose and impose our way of life on others. Instead, we helped build institutions such as this one to defend the sovereignty, security, and prosperity for all.”

This genuine win-win approach fueled the greatest explosion in prosperity the world has ever seen. This prosperity spread naturally around the globe to countries that opted to join the world economy. The opportunity was seized. Great powers did not dole it out as some kind of imperial largesse.

Our approach reflects a view deeply ingrained in American thinking that fair play is about genuine win-win arrangements. Everyone can benefit if the rules are obeyed. Life is not necessarily zero-sum. My being strong or prosperous does not require you to be weak or poor.

This is also how we conduct international relations. We don’t think we’re weaker or poorer just because someone else in the world simply makes money or has power. On the contrary, we think the insights of others can benefit us, that the power of others can make the world a safer place, and that the wealth of others means they’ll make things we want to buy and buy things we want to sell. Such positive-sum, synergistic thinking is inherently pluralistic.

This is why the U.S. never sought exclusive power in Asia or the world. With the collapse of Soviet Communism in 1991 the United States became (at least for a time) the world’s only so-called superpower, but we didn’t use our position to keep other countries down. On the contrary, we have invested substantially in the growth of other countries – including China, Japan, India and others – to bring about greater wealth and prosperity elsewhere, not only at home.

This is pluralism – or, in political science terms, “multipolarity.” We don’t fear or oppose such multipolarity. On the contrary, we’ve cultivated it. We want other countries to play important roles in world affairs, to respect a shared set of international rules, and to share the burdens of keeping the world safe and secure.

The U.S. does not oppose the growth in power and prosperity of other countries. We don’t view it as a zero-sum matter or a threat. Just ask Deng Xiaoping!

As the historian John Pomfret records, when Deng was flying to the U.S. for his historic first visit after normalization in 1979, his foreign minister asked him why he picked the U.S. for his first trip as leader. Because, Deng said, America’s allies are all rich and strong, and if China wanted to be rich and strong, it needed America.

There’s a lesson here, too, about China’s own experiences with pluralism.

China was on a better trajectory in its era of reform and opening, when it moved toward greater pluralism in politics and policy.

This I witnessed firsthand in that scratchy dumpling shop near Qian Men. At that time many were fond of quoting Deng Xiaoping’s very practical idea that it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice. “Let 100 Flowers Bloom!”

More pluralism and less authoritarianism would be better for the Chinese people and better for the world. A less authoritarian China would likely be less aggressive overseas.

But the increasing authoritarianism is reflected in this New Type governance idea, in the region and beyond.

BEIJING’S VIEW OF ‘PLURALISM’

On Beijing’s “new type” governance idea, PRC officials have spoken for themselves. I think then-foreign minister Yang Jiechi summed up Beijing’s view of regional order in 2010, when he declared to an ASEAN meeting: “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.” For Beijing, international relations is about hierarchy and big-makes-right. It is not respectful of pluralism or sovereign autonomy.

Inside China, the Communist Party increasingly enforces political, racial, cultural, digital and ideological homogeneity. As is increasingly apparent in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and beyond, Beijing’s idea of governance is enforcement of uniformity.

And at the global level, what is Beijing’s view of pluralism? Consider how it responded when a single NBA executive tweeted an unwelcome opinion about Hong Kong. Clearly Beijing’s campaign to compel ideological conformity doesn’t stop at China’s borders.

THE ‘CHOICE’ BEFORE US

Before closing, I’d like to address the close relationship between pluralism and choice.

If a pluralistic world is one in which countries have the freedom to be themselves, that means they have the freedom to make choices. Pluralism and choice go hand-in-hand.

Now let’s consider the commonly heard concern that countries will be forced to choose between the United States and China. I want you to know, they won’t be forced to make such a choice by the United States. When we say that America’s vision is pluralistic and inclusive, we mean it, and our record shows it. We aspire to friendly relations with Beijing and have no objection if other countries similarly strive to deal with Beijing in cooperative, cordial ways.

In our foreign relations, though, all countries constantly make many choices about policy issues—economics, trade, technology, security, etc.—that affect their interests and well-being. We encourage our allies and partners to choose prudently, in ways that protect their sovereign national interests.

Sovereignty means the ability to live free of foreign domination, to live according to one’s own laws and make one’s own decisions. We’re not looking to dictate to others, and we want our allies and friends not to be subject to anyone else’s dictates.

Choosing for sovereignty is important because without it, the freedom to choose at all could be lost. Choices that preserve sovereignty are choices that preserve the future freedom of choice, which we all cherish. A region in which countries maintain their freedom of choice is a pluralistic region, and will be a more prosperous and secure one.

CHINA’S PLACE IN OUR PLURALISTIC VISION

I’ll close by returning to our policy. It has long been America’s view that the postwar international system is sufficiently resilient and adaptable—sufficiently pluralistic—to accommodate and gladly incorporate a strong and prosperous China that plays by the rules that have served the world well for 70 years. This system is capable of change, and has in fact adapted to many ideas and pressures not imagined decades ago.

It remains our hope today that Beijing will return to the path of reform and convergence. More respect for pluralism, at home and abroad, would be a welcome sign.

●【卡神遭起訴】柯文哲知道「誰出錢」 韓國瑜:盯緊綠營怎解釋

熱門影音

熱門新聞

- 【懶人包】勞動部公務員疑遭職場霸凌輕生 事件始末「時間軸、手段、調查結果」一次看懂

- 起底謝宜容!傳身家背景雄厚「善做公關」 先生和綠營高層有交情

- 一元特典!YOASOBI「超現實」小巨蛋演唱會釋出「零星票券」,11/24 採實名制一般販售

- 【世界棒球12強賽】滿足「2條件」台灣確定晉級4強 今晚是關鍵

- 先搶先贏!Ado 五月林口體育館演唱會採實名制入場,11/19 輸入「指定代碼」可優先預購

- 【內幕】T112步槍裝彈器採購案疑專利侵權 以色列向軍備局寄存證信函

- 楊冪人氣暴跌與《慶餘年》張若昀演新片淪鑲邊女主 造型曝光全網夢回《三生三世十里桃花》

- 王一博金雞獎典禮被抓包視線離不開趙麗穎 網揭兩人4年戀情無法曝光背後真相